Madeline Watkins describes academic analyses on the growing connections between social and criminal justice policy.

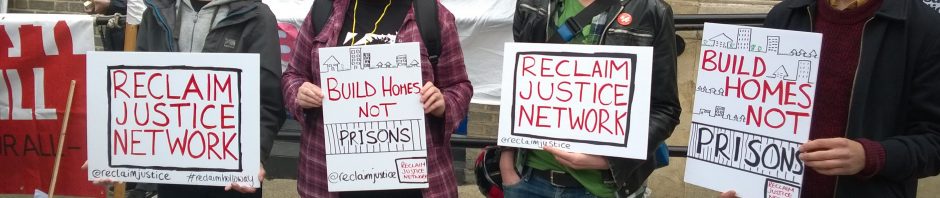

In trying to capture the essence of current penal policy Rebecca Roberts has described an ‘invasion of criminal justice ethos into social policy’ whereby housing, employment, education and border control are ‘operating on punitive principles and often funnelling more people into the criminal justice system’ (see here). In academic debates this has sometimes been described as the ‘criminalisation of social policy’.

What is the ‘criminalisation of social policy’ and how have recent changes in welfare, workfare and criminal justice been explained by academics? Drawing on the work of John J Rodger (Rodger, 2012) I outline contemporary academic analysis to try and frame and describe recent policy developments.

Criminalisation

The criminalisation of nuisance behaviour, behaviour that was previously ‘annoying but legal’ is one example of the encroachment of criminal justice on social policy. Issues such as noise in residential areas, large nuisance gatherings, and good parenting have all been brought under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system. What was once regarded as a social problem has now been recast as a criminal justice issue with perpetrators being disciplined by the ‘threat’ of punishment (Rodger, 2012). Rodger argues that the structural coupling of the criminal justice system and welfare for the purposes of behavioural control has resulted in a criminalising tendency, which is at the very heart of how contemporary welfare systems work today.

The Big Society

Rodger takes the idea of the ‘Big Society’, the flagship policy of the Coalition, and highlights how it has resulted in the net widening of the criminal justice system. This policy, based on the ‘gradual removal of a social safety net’ (Rodger, 2012), has led to the division of society into clearly established groups of insiders and outsiders, with those most at risk, more vulnerable citizens criminalized and alienated (Esping-Anderson, 2002).

The notion of the ‘Big Society’ rests on a vision of a society ‘populated by enterprising and educated citizens who are responsible for themselves and their families, and eager to engage in productive work for Britain plc’ (Rodger, 2012). The family is charged with nurturing and preparing the next generation for its role as citizen workers in a post-welfare society. Families that fail to live up to this task, families in which children are not being adequately prepared for their future citizen-worker status effectively, are immediately categorised and labelled ‘dysfunctional’, ‘troubled’ and ‘problem’ families.

The ‘Big Society’ involves the contracting out of welfare to the voluntary sector in poorer communities, housing estates and inner city areas. Rodger describes the ‘hollowing out’ process which has occurred, with the State using the assets of civil society to meet social and criminal justice objectives while committing a minimum level of resources. This has caused the boundaries between caring and controlling forms of intervention to become perilously blurred. The inevitable imposition of regulation, performance targets and professional practice requirements has resulted in the re-orientation of welfare policy into an instrument of behaviour management by explicitly linking ‘civility’ with citizenship rights (Rodger, 2012).

Regulating the poor

Rodger’s work reveals how Britain has been transformed from a welfare state, to a ‘social investment state’, in which social policy is used against those not fully engaged active citizenship. Local neighbourhood populations have been driven into schemes whose latent purpose is the management of delinquency; anti-social behaviour, ‘inferior life trajectories’, and nuisance behaviour are all outside the expected norms of active citizenship and are behavioural dispositions requiring control. Rodger highlights that ‘governing through crime’ (Simon, 2007) ‘cultures of control’ (Garland, 2001), and the ‘penalization and punishment of the poor’ (Wacquant, 2009) amount to what is now the normal working of contemporary Western welfare systems.

Madeline Watkins is an intern at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies and BA History student at University College London.

References:

Esping-Anderson, G. (2002), a Child-Centred Social Investment Strategy. In G. Esping-Anderson et al (eds.), Why We Need a New Welfare State, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Garland, D. (2001), the Culture of Control, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Rodger, J. (2012), ‘Regulating the Poor’: Observations on the Structural Coupling of Welfare, Criminal Justice and the Voluntary Sector in a ‘Big Society’, in Social Policy & Administration , Vol. 46, No. 4, August 2012, pp.413-431

Simon, J. (2007), Governing through Crime: How the War on Crime Transformed American Democracy and Created a Culture of Fear, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wacquant, L. (2009), Punishing the Poor: The Neo-Liberal Government of Social Insecurity, London: Duke University Press.

Reblogged this on Matthew Baker and commented:

Great Article on the Re-Definition and Regulation of the Poor! By Mads Watkins